History of Gyokusendo

The Echigo plain.

The Nakanokuchi and Shinano Rivers run like threads stitched through the rice paddies.

In the distance, Mount Yahiko looks over the land.

The mountain and the copper found within transformed Tsubame-Sanjo and brought it to life with the sound of hammers.

For us, this everlasting sound is a tribute to the life given to us and a pledge to continue our work for many more years to come.

In the early Edo period (1603 - 1868), the Shinano River, which flows through Tsubame-Sanjo, was flooded nearly once every three years and agriculture as well as the lives of people suffered enormously. The prefectural governor during this period hired a blacksmith from Edo (present-day Tokyo) to live and work in the region and teach local farmers how to produce Japanese nails (wakugi). As time went on, what started as a side business in bad years, slowly became the main source of income for more and more people. The use of hammers in Tsubame-Sanjo was taking root.

Demand for nails steadily increased as Edo constantly faced the need to rebuild from frequent fires and natural disasters. Tsubame-Sanjo gradually developed as the foremost nail producing region in Japan.

As early as the 1650s, artisans in what is now present-day Tsubame were being commissioned to make copper fittings and other ornaments for shrines. By 1700, with the discovery of copper in the neighbouring mountain of Yahiko, copper ornaments would become as common a specialty as iron nails. It is believed that the Tamagawa family had specialized in this sort of work three generations before Gyokusendo's establishment.

Copperware: Tools of Use

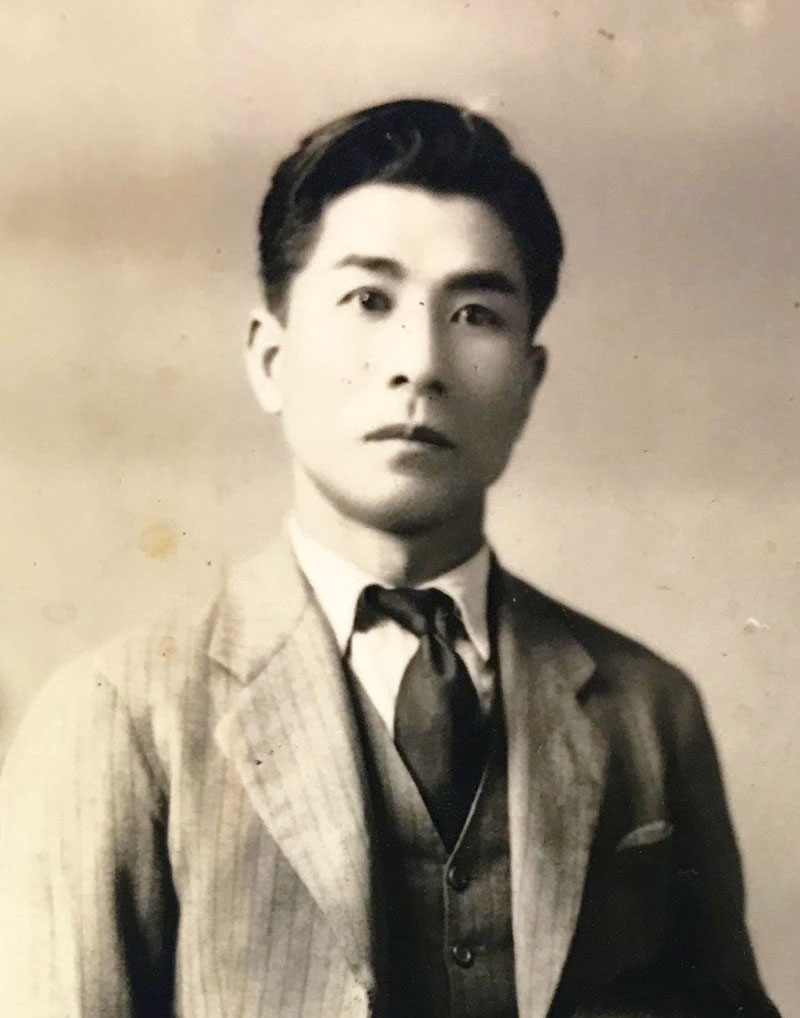

Kakubei Tamagawa, Founder

(1799-1871)

The diffusion of metal working techniques particularly in copper fixings for shrines and iron nails (wakugi) meant that Tsubame was establishing itself as an area built by the hammer. Just as a steady supply of copper was being mined from Mt. Yahiko, an artisan named Toshichi left Sendai, crossed the mountains and settled in Tsubame in 1768. He brought with him tsuiki, the hammering technique by which a vessel is created from a copper sheet.

This hammering technique was eventually passed down to Kakubei Tamagawa who founded Gyokusendo in 1816. He became known by locals as "Yakanya Kakuhei" (Kettle Maker Kakuhei) as he and his apprentices established themselves as makers of household items such as kettles, pots, and wash bins.

Kakubei Tamagawa, Founder of Gyokusendo

Early-to-mid 1800s

In Niigata during the mid-to-late Edo Period (1603 - 1868), copperware had become one of the largest artisanal industries, second only to textiles. At this time, businesses with more than 5 people were considered big and there were 8 such companies working in textiles, 3 in copperware, and 2 in casting.

By the Meiji era (1868 - 1912), the only copperware workshop that had more than 5 artisans was Gyokusendo.

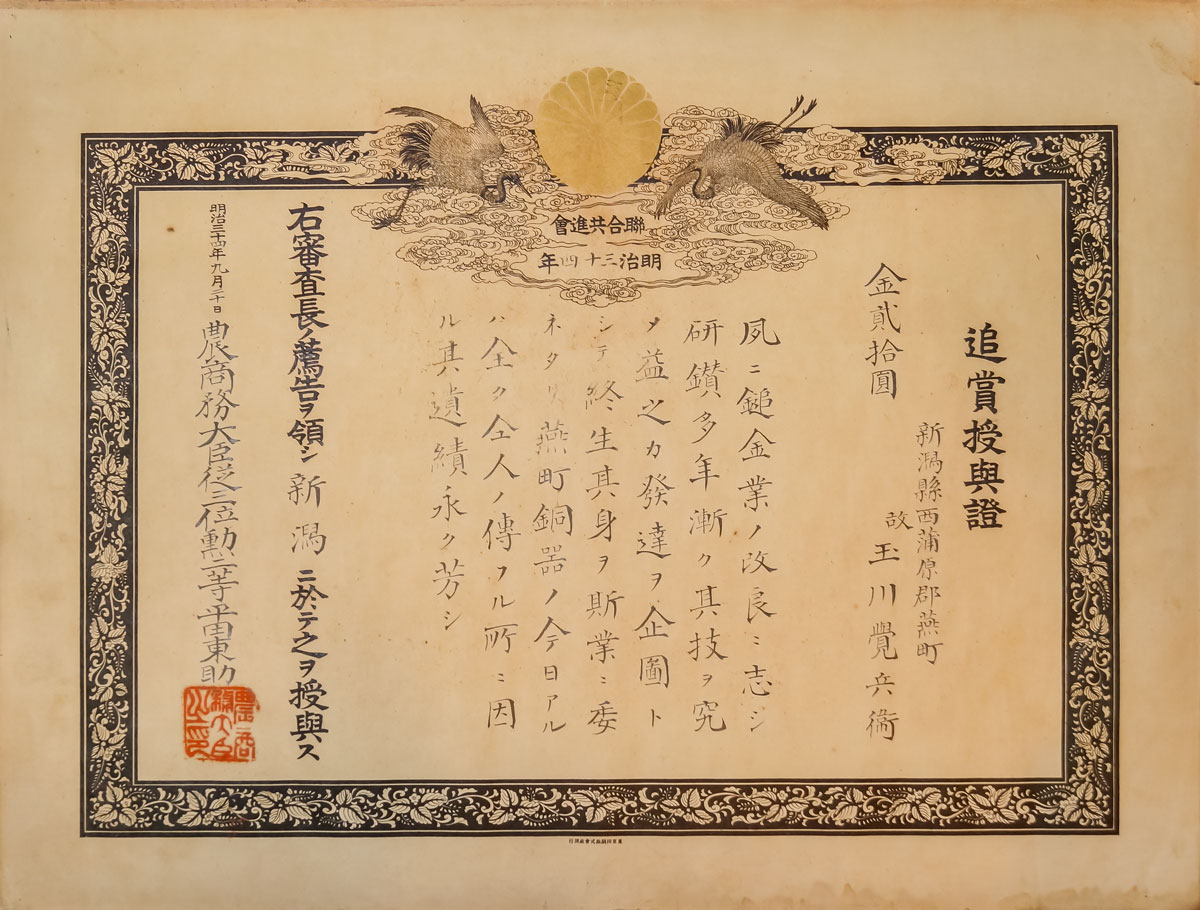

In 1901, the Minister of Agriculture and Commerce recognized Kakubei Tamagawa posthumously for his contribution to the establishment of Tsubame's copperware industry.

From Tools of Use to Works of Art

Kakujiro Tamagawa, Second Generation Head

(1829-1891)

In 1868 the Meiji government instigated large shifts in the metal working and other artisanal industries.

The government actively sought to include these industries in international expositions in order to gain attention and drive exportation. This would help the acquisition of resources to drive industrial growth throughout the country.

Responding to this, many producers who had been primarily making simple items for daily use, shifted focus to creating pieces that would showcase aesthetics and skill in craft. Gyokusendo was among the first workshops to make their international debut, presenting their works to showcases all over the world.

Kakujiro Tamagawa, Second Head

Early Meiji Period (1868 - 1912)

Riding on the momentum of the Meiji government's initiatives, Kakujiro would set out to create works worthy of international praise. In 1873, Japan would make its international debut at the World Exposition in Vienna and Kakujiro Tamagawa's pieces would be among those on display. The small workshop that his father established in 1816 took the name Gyokusendo for the first time.

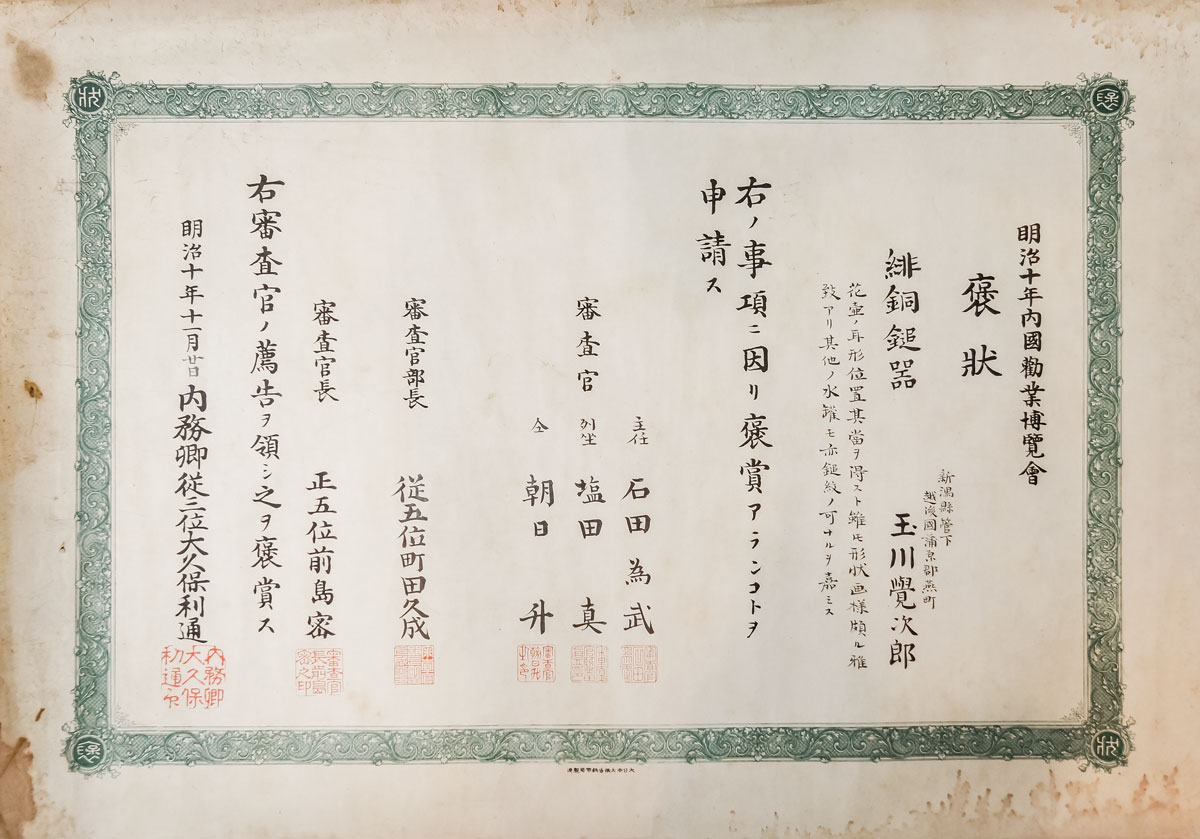

After Vienna, Japan became a regular participant at expositions overseas. The Meiji government even commissioned such events domestically and so the level of Japanese craft continued to evolve year after year.

Gyokusendo for its part participated in expositions both domestically and abroad and contributed greatly to that technological evolution.

Pushing the Bounds of

Tsuiki Copperware.

Craftsmanship to Fascinate the World.

Kakuhei Tamagawa, Third Generation Head

(1853-1922)

In 1882, Kakujiro’s eldest son, Kakuhei, became the third head of Gyokusendo at the age of thirty.

Encouraged by the government, local producers continued to submit their works to expositions all around the world and Gyokusendo had been chosen to represent Japan in metal work. Kakuhei, however, was concerned that the techniques used currently in Tsubame were not enough to really compete on the world stage.

Continuing where his father left off, Kakuhei wanted to incorporate even more new ideas and techniques into Gyokusendo. The change of leadership was the impetus needed to really shift gears.

Kakuhei Tamagawa, Third Head

1890

Kakuhei sought to not only master the hammering techniques of the previous generations before him, but also successfully incorporate decorative techniques into copperware as well.

He commissioned Katei Taki (滝和亭), a Nanshu painter from Tokyo, and Ungai Kaeriyama (帰山雲涯), a Japanese traditional painter from Sanjo, to create the engraving designs. He then applied an unorthodox technique of using only hammers and anvil stakes to emboss the designs.

Kakuhei believed that in order to further advance the artisans' craft, it was necessary to incorporate techniques and methods from regions other than Tsubame and Sanjo.

The Sword Abolishment Edict of 1876 led to the unemployment of many sword smiths and engravers throughout Japan, including southern Niigata's castle town of Takada (present day Joetsu city). There he recruited a number of tsubashi, artisans who specialized in the creation of intricately designed handguards. To guide their work he also invited a leading engraver from Tokyo to act as foremen. A plating expert was brought in to further develop Gyokusendo's colouring processes.

The workshop itself was expanded to accommodate the increase in artisanal manpower, and with its completion in 1890, Kakuhei thought Gyokusendo was finally ready for another attempt at international recognition.

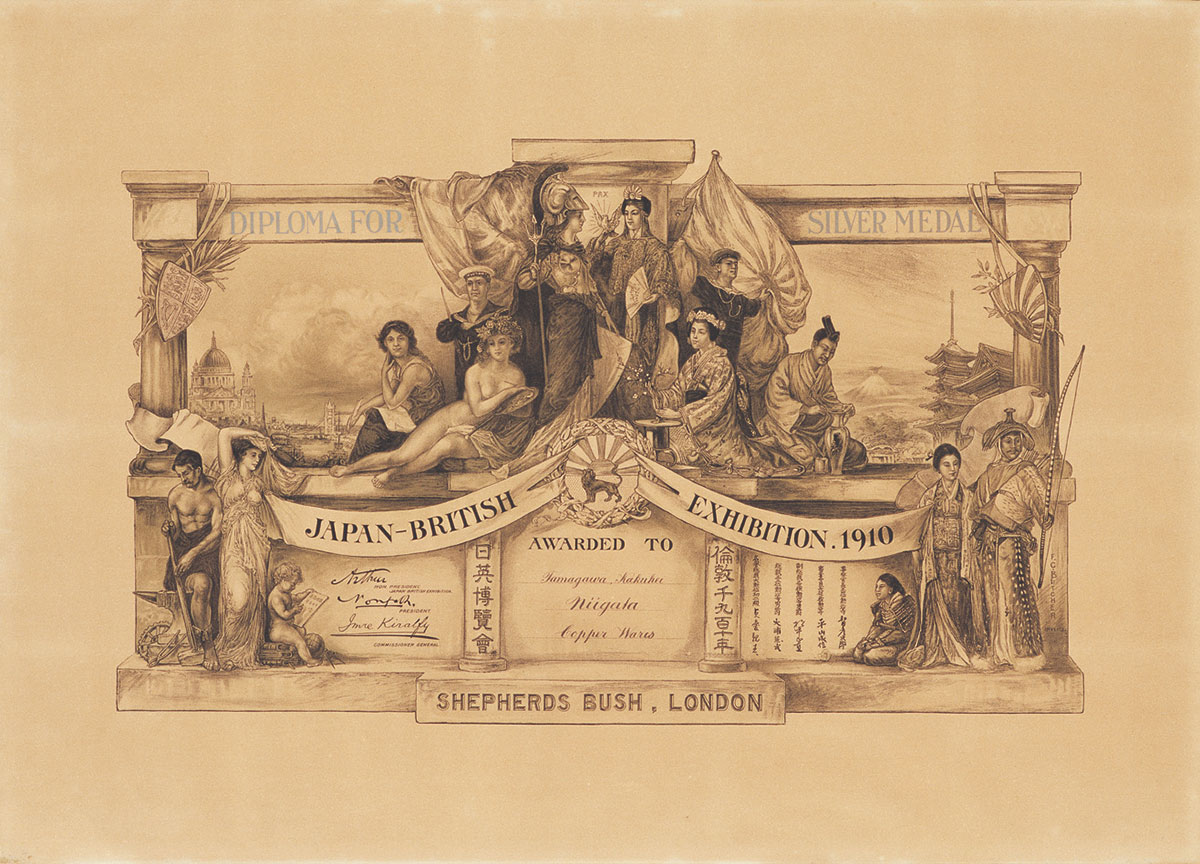

Gyokusendo produced piece after piece of exquisite craftsmanship and international recognition quickly followed. Most notable accolades include a bronze medal at the Columbia Exposition in Chicago (1893) and silver medals at both the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (1904) and Japan-British Exhibition (1910).

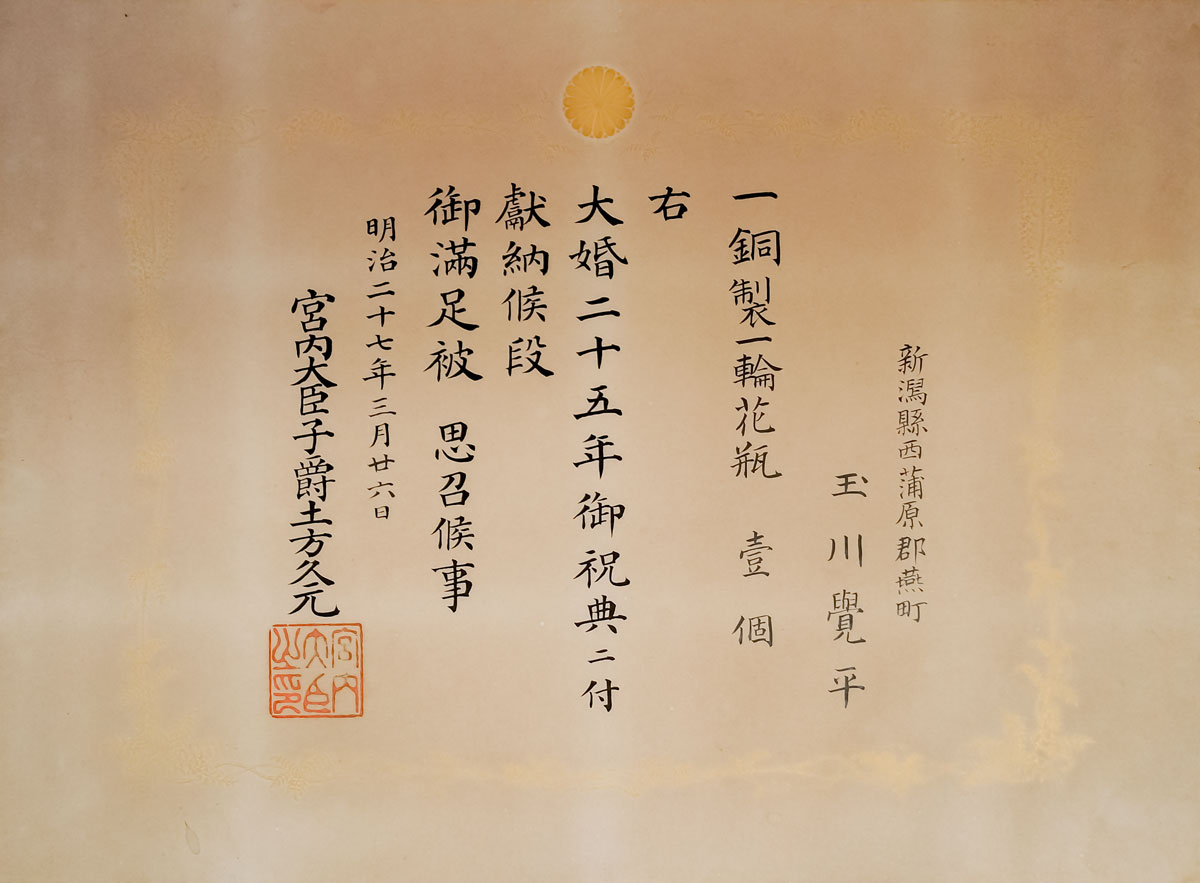

By 1894, Gyokusendo had already started to make a name for itself and so the Third Head was invited to present works to the Imperial Family in celebration of their 25th Wedding Anniversary. Since then, it has became customary for Gyokusendo to present gifts to the Imperial Family on auspicious occasions, most recently in 2019.

The Third Head, Kakuhei Tamagawa, strived to train apprentices and contributed his time and energy to the development of the copperware industry.

A picture taken in the front garden of the workshop with current and independent artisans in summer, 1922.

A picture taken in the front garden of the workshop with current and independent artisans in summer, 1922.Front row, third from the left:

Kakuhei Tamagawa (Fourth Head)

Kakuhei Tamagawa (Third Head)

Momi Tamagawa (Wife of the Third Head)

Product Modernization, Artistic Refinement, and Devotion to Innovation

Kakuhei Tamagawa, Fourth Generation Head

(1881-1947)

Successive awards at international expositions led by the engravers from Takada and Tokyo contributed to a long period of success for Gyokusendo. As these artisans got older and started to retire, however, it became apparent that without training younger apprentices to take their place, their expertise was in danger of disappearing.

Rather than inviting more engravers from outside the company, the Third Head Kakuhei thought the best way to pass down the techniques was to train someone within the family. He apprenticed his eldest son, Kentaro, to Imperial Household Artist Unno Shomin and later even enrolled him in the Metal Engraving Department at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts (present-day Tokyo University of the Arts).

In 1904, Kentaro returned to Tsubame having studied with the leading masters in the discipline and sought to apply what he learned to the development of new works.

Kakuhei (Kentaro) Tamagawa, Fourth Head

1921

Kentaro, like his father before him took the hereditary name Kakuhei and became the 4th Head of Gyokusendo, eventually leading the workshop to win the top prize at Philadelphia's World Fair in 1926.

Receiving the top prize was the achievement of a long held goal and affirmation that their level of skill was among the best in the world.

The dedicated artisans taking after the Fourth Head's industriousness helped lay the ground work for many of the works iconic of the brand today.

One of the great developments during this time was the 'seamless spout,' a technique by which artisans could create a kettle or teapot body and spout, together from one sheet of copper. The ingenuity and skill required to complete this became widely talked about not only in copperware, but in other traditional crafts as well.

Colouring fundamentals also take root at this time under the Fourth Head. The techniques, which are still used today, create unique colours that grow and deepen with use.

The evolution of colouring techniques in combination with shaping allowed artisans new possibilities to express their craft. This was a development that allowed not only Gyokusendo but the copperware industry as a whole to add another page to the history books.

Despite the success, however, the Great Depression that would devastate the United States in 1929 would hit Japan not a year later and many of the copperware artisans in Tsubame would take up jobs in construction, just to make ends meet.

If Gyokusendo relied solely on the market in Tsubame, it would likely lead to its demise. It was then, in 1930, that the Fourth Head reached out to an ally, Tatsuji Suzuki, the principal of Yokohama Technical School (present-day Yokohama National University). With his help, Gyokusendo would establish a branch workshop in Yokohama as a last-ditch effort to stay afloat.

From War to Reconstruction

Kakuhei Tamagawa, Fifth Generation Head

(1901 - 1992)

Since the Fourth Head had no children, his younger brother, Johei, took the name Kakuhei and became the Fifth Head of Gyokusendo in 1930. He travelled with five other artisans from Tsubame to Yokohama to help establish a branch workshop.

A city of few traditional crafts at the time, Yokohama became a strong supporter of Gyokusendo and helped encourage the growth of hand-hammered copperware in the region.

In commemoration of the opening of the workshop, the city presented a gift made by Gyokusendo to the Kaninnomiya Family, a branch of the Imperial Family. Another gift was presented to the Empress the following year.

Kakuhei Tamagawa, Fifth Head

1930

While managing the Yokohama workshop, the Fifth Head devoted his time and energy to building strong connections with local department stores by travelling all over the greater Tokyo area and surrounding prefectures. Familiarity with the brand slowly grew.

More artisans were brought on at home in Tsubame as well as in Yokohama with the intent of further increasing production and expanding sales channels.

Success was short lived. In 1937, war was officially declared between Japan and China. Restrictions on the use and purchase of copper as well other metals made it near impossible to continue production.

Taking advantage of its superior tensile strength, aluminum was used as an alternative to make decorative plates. This effort too was all for not as Gyokusendo found itself helpless with the Japanese economy in a steady downspin.

Kakuhei Tamagawa, Fifth Head

Kakuhei Tamagawa, Fifth Head

As war intensified, the Japanese government strengthened the Metal Collection Act forcing the Yokohama branch to close. The following year in 1943, Tsubame too was shut down and all the craftsmen discharged.

Kakuhei was at a loss, but he was driven to move forward. He assembled craftsmen that had a familiarity with steel and established the Tsubame Aviation Company to build airplane parts for military aircraft.

When the war ended in 1945, Kakuhei spent the next couple of years calling back the artisans and starting operations again in Tsubame.

The situation was unstable however and a spike in the trading price of copper would again threaten to put Gyokusendo out of business. Kakuhei approached Niigata Prefecture so as to be recognized for the uniqueness of their craft. Then in 1958, Gyokusendo's tsuiki copperware was designated as an Intangible Cultural Asset by Niigata Prefecture.

The economy gradually improved and traditional crafts became more popular. Slowly but surely, more artisans returned and finally the rhythmic sound of hammering copper could be heard in Tsubame once again.

An Artist at Heart,

Building Bridges and Pushing Tradition

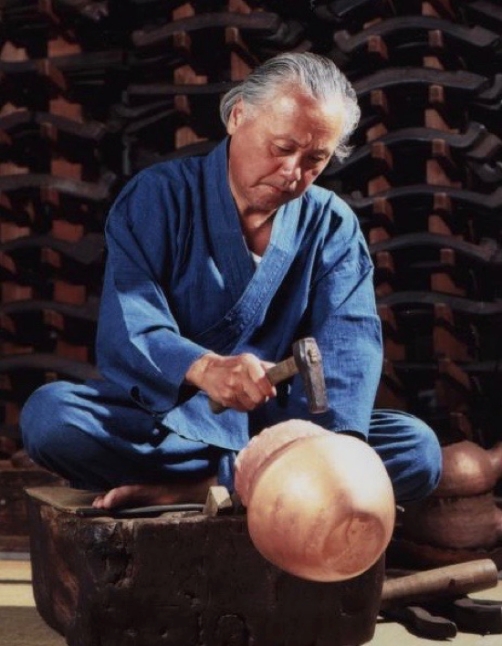

Masao Tamagawa, Sixth Generation Head (1938–)

After joining the company, the Sixth Head Masao, worked tirelessly to hone and develop his skill, contributing to the development of Gyokusendo's teaware and other works.

The Sixth Head, as well as the other artisansーpast and presentーwere taking part in the succession of knowledge that now spanned over 160 years and six generations. The uniqueness of the tsuiki copperware craft as well as the long history of which it had accumulated, earned it recognition by the Japanese government once again. In 1980 the Agency for Cultural Affairs designated it an Intangible Cultural Property.

Masao Tamagawa, Sixth Head

1985

The Sixth Head greatly bolstered copperware craft in Tsubame and its neighbouring town of Bunsui (amalgamated into Tsubame city in 2006). In 1981 he established and led the Tsubame-Bunsui Copperware Cooperative with copperware artisans from both towns forming its core membership.

In contrast to artisans from Tsubame, Bunsui artisans had been influenced heavily by the copperware made in Kyoto, which was typically more refined and delicate in nature. Tsubame, with its tradition of pounding out copper sheets from ingots, had developed a more rugged and dynamic style. Through this cooperative, artisans from both sides engaged in mutual exploration and exchange with one another.

That same year, Tsubame's copperware craft was designated nationally as a Traditional Handicraft by the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (presently the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry) and the sharing and exchange of craft know-how even across other disciplines became common all over Japan.

Masao Tamagawa, Sixth Head

Masao Tamagawa, Sixth Head

"trace"

"trace"

Masao Tamagawa, Sixth Head

1968

In addition to the Sixth Head's contributions to building networks, he was a fervently passionate artist who received numerous accolades from local as well as national exhibitions. Locally, his work earned him the Top Prize at the Niigata Prefecture Fine Arts Exhibition. Nationally, his works were selected for inclusion in the prestigious Japan Fine Arts Exhibition as well as won him the Top Prize administered by the Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology at the National Selections Exhibit.

While his father, the Fifth Head, excelled at manipulating sheets of thick metal, the Sixth Head had acquired a level of skill with thin sheet metal not achieved previously. The delicate and flowing forms he was able to create came from his keen use of hand-held burners and his uncanny ability to create shapes thought not to be possible by the hammer.

During this time, Gyokusendo's copperware had become a prominent symbol of traditional craft in Niigata. The company was often commissioned to make commemorative gifts for companies or individuals. The workshop even needed to hire more hands to satisfy demand.

Local retailers and wholesalers in Niigata drove interest for Gyokusendo pieces outside of Niigata as well. Tsubame tsuiki copperware became an item of choice for special occasions all over Japan.

However, prosperity and growth of the workshop would suddenly come to screeching halt. The economic bubble burst and the subsequent stagnation of the Japanese economy of the early 1990s meant that the demand for such commemorative gifts drastically declined. Gyokusendo would face an economic crisis not felt since wartime.

In 1995, the Sixth Head made the heartbreaking decision to let go many of the artisans he had helped train. Of the thirty artisans, just fifteen remained. With their backs to the wall, the remaining artisans carrying generations of knowledge and skill fought to nurse the workshop back to life.